Wednesday, April 24, 2024

Tuesday, April 23, 2024

Listen to What the Man Said

Listen to What the Man Said

Written by Timothy Swallow

Gold Magazine

1978

Paul McCartney's song "The Mull of Kintyre," recorded and released in December of 1977, is the biggest-selling record of all time in Great Britain. Notching up an unheard-of sale of over twenty thousand copies a day, the record went on to sell in excess of two million copies in a mere five weeks. It became the world's fastest-selling single. It outstripped the previous sales record held by the Beatles by more than four hundred thousand copies. McCartney, who wrote, sang, produced, and published "Mull," earned himself 400,000 pounds in those astonishing five weeks.

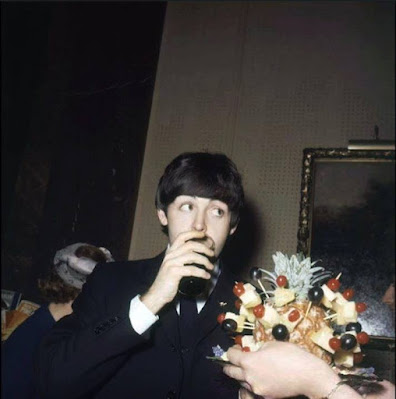

I met Paul McCartney in Scotland, in Aberdeen, on a drizzling Easter Sunday afternoon. We sat - he jovially sprawled, I tensely ill at east, in an otherwise empty hotel restaurant. Mccartney wears faded denim jeans, a jokey campus sweatshirt, and a humorous half smile on his face. Although his air of boyishness remains, his face has changed since it so engagingly graced the cover of "Meet the Beatles" back in '62. The looks are beginning to slide. The high rounded cheekbones now slope downwards, when once they stretched tautly up. The delicate kiss-me-slowly lips have no set into a firm business-like line, although they still curl good-naturedly at the corners. The eyes, those celebrated lash-fringed orbs, have something more than their original bovine limpidity. Now set into a grid of laughter lines, they reflect a rich depth of experience, alert and amused and never once cynical under the fly-away wings of those famous arched eyebrows. So this is Paul McCartney...

He is anxious to talk about the phenomenal success of "Mull" and to tell me about the recording session he was recently involved in for "London Town." I asked him, over a cooling pot of Typhoo, how the recording of "Mull" - now a new Scottish anthem- came about.

"The idea just happened while I was on my farm in Scotland. Though most Scottish songs you hear nowadays are old tunes that people redo or comedy songs like 'Up Your Kilt." I wanted to do a sort of traditional Scottish ballad. I wanted to do a Scottish song for a long time. A song you could sing when you and the family get together. It's hard to do nowadays because people don't go "Hoots mon" in the heather anymore. But I actually live up there in the Mull of Kintyre, and I like bagpipes. It's a song I'd like to hear the football crowd at Hampden Park sing. That'll cause a roar! I didn't see it as a single myself, but one of the lads in the band said it would be great, and the people in the business kept telling me to think of the exiled Scots audience. But I never realised how many Scots there were! I didn't think there'd be enough to go around."

"Although people say all I'm after is commercial success, I never really think of how a record is going to do when I'm writing it or recording it. Wings have had a couple of number twos, but it's great to have a number one. You always wonder what a record is going to do when it's released, and if it's a flop, you wonder if it was worth it."

McCartney's solo career since the dissolution of the Fab Four has not always been gilded with the sort of success that "Mull" finally brought him.

"The way we were treated by the rock press over "Wild Life" really hurt me. I only try to please people, and I was upset by the way they savaged us as if they were getting their own back at me for all the success I had with The Beatles in the past. The critics expected something all intellectual and stuff. They really came down on me for that one. Let's face it: critics never liked the big stuff in history. They never liked Van Gogh's pictures and has he got a name? I don't go for analysis myself. A lot of singers do. A lot of them go right into it. I prefer to sweat it out."

McCartney turned the corner with the second Wings album, "Red Rose Speedway." Even his most hardened critics could not deny the sheer sense of fun with which the album sparkled. "My Love," the single taken from the album, gave Wings their first major hit, and the song itself went on to become a cabaret standard. By this time, the division was obvious: the more the public began to tune into McCartney's sentimental appeal, the less favourable the reviews became.

Critical approval did come, however, from a rather unexpected source; McCartney and his band found themselves in Hollywood for the 1974 Oscars ceremonies for which they had received a nomination for their musical score to the James Bond flick "Live and Let Die." But even there, the nomination was not followed by the award itself, and McCartney returned to Scotland disappointed.

An early tea arrives in the shape of a mountain of Shepherds Pie and a forest of chips. McCartney nips his cigarette and tucks into his tea with relish. I judge the time right to ask him why he has not elected to move to a tax-haven retreat.

"I can't stand the idea of living where it's convenient for money. We like Britain, and it's a great place for bringing up the kids." (He has two younger daughters, Mary and Stella, and a six-month-old son, James Louis.)

"The thing about having a bit of money is that you can live wherever you want to live. I've seen 'em all in LA and places, all these tax-exiled rock stars, loads of money in the bank, but they're all as miserable as fuck. Having a life with my family is important. I had a happy home life in 'Pool when I was a kid, and I guess that's what I'd gone after. Finding it is pure luck, and I've been lucky. I've got warmth and contentment..."

As I look up from my notepad, I am hit for the first time by the charisma of this man. Preoccupied by the strain of traveling and coordinating this interview, I had not at once perceived the aura that surrounds him. His easy confidence, his good humour and readiness to talk seems at first at odds with his status. A status, incidentally, that can in no way be underestimated. But then I realized his good nature is not incidental to his fame, wealth, and success; it is their root. McCartney is not a spoiled egoist living in a penthouse ten miles high. He is a musician who lives with his family on a farm. Paul McCartney, that adored and adorably mop-top, is now a contented man. Sales figures aside, this contentment itself is no mean achievement.

"I don't want to be some great superstar because you start to believe your own legends. So I'll just be myself and not be like Howard Hughes." He opens his wide eyes even wider. "You can get trapped in that tinsel and glitter and stuff, like Rod Stewart. I'm sure he doesn't really want to be like that. The first thing you want to do when you see someone on a pedestal like that is knock 'em off, isn't it?" I ask him what he thinks of his more errant former colleges.

"The others and I get on reasonably well. You don't hear about their records so much, but they're still making them."

And, finally, what doe the future hold for a man who can earn 400,000 in five weeks?

"I have an ambition to play small places with the band. I want to get the atmosphere of the free man on the street. Places like "Joe's Cafe." I'll ask the audience for requests."

"The main thing is the music. It's not the bread, it's not the fame, it's not even the reviews. It's down to whether you like the music or not. And what I'm doing now." McCartney declares emphatically, "I like."

Monday, April 22, 2024

Ringo at the gallery

April 20, 2024 - Ringo is hitting the promotional rounds for this Cooked Boy EP. Here is he recently talking at the Morrison Hotel gallery talking about Let it Be, drumming and his new EP.

.jpg)